Notes: The Psychology of Money

The big takeaway from ice ages is that you don't need tremendous force to create tremendous results.

The Psychology of Money

Introduction: The Greatest Show on Earth

Money has little to do with how smart you are and a lot to do with how you behave.

That's how a techie, who got rich by inventing a wifi router, spends money and soon gets insolvent.

On the other side, Ronald Reed, former janitor left 2 million to his step kids and 6 million to charity.

There was no lottery win, he saved what little he could and invested; then waited for decades

on end, as tiny saving compounded into more than 8 million.

In what other industry does someone with no college degree, no training, no background,

formal experience and no connections massively outperform someone with the best education/training/connections.

We are taught money too much like physics and not enough like psychology (with emotions and nuance).

Chapter 1: No one’s crazy

Your personal experiences with money make up maybe 0.00000001% of what’s happened in the world, but maybe 80* of how you think the world works.

- People from different generations, raised by different parents, who earned diff incomes, born into diff economies, diff job, diff degrees of luck, learn different lessons.

- What you have expereinced is more compelling than what you learn second-hand.

- What seems crazy to you may make sense to me.

- Equally smart people have diff reasons why recession happens, how you should invest, what you should prioritize, how much rise tou should take and so on.

- We all think we know how the world works but we've all only experienced a tiny sliver of it.

- In theory, people make investments based on their goals but that's not true, they make as per their experiences they had in their own generations, specially early in their lifetime.If you grow up when stocks were strong, you invest more in stocks.

- Individuals willingness to bear risk depends on personal histoory, not intelligence / education / sophistication, just the dumb fact of when/where you were born.

- Every financial decision a person makes, make sense to them in theat moment and check the boxes they need to check. They tell themselves a story about what they're doing and why. That story has been shaped by their own unique experiences.

- Modern financial system is just 50 years old, yet we expect ourselves to be perfectly acclimated.

Next Chapter: How Bill Gates got Rich.

Chapter 2: Luck and Risk

Nothing is as good or as bad as it seems.

- Bill Gates with the luck of 1/million got rich but his friend with 1/million died in a mountaineering.

- Eg. Let's say I buy a stock and five years later it's gone nowhere. It's possible that I made a bad decision or I made a good decision which had an 80% success rate but end up on unfortunate 20%.

- Now how to know which 20% or which is just a bad decision. It's possible to statistically measure but we don't, we just prefer simple stories which are easy but often misleading.

- The difficulty in identifying what is luck, what is skill, and what is risk is one of the biggest problems we face when trying to learn about the best way to manage money.

- Be careful who you praise and admire. Be careful who you look down upon and wish to avoid becoming.

- Not all success is due to hard work and not all povertly is due to laziness.

- Focus less on specific individuals and case studies and more on broad patterns.

- Extreme examples are often the least applicable to other situations.

- The trick when dealing with failure is arranging you financial life in a way that a bad investment here and a missed financial goal there won't wipe you out and you can keep playing.

Next Chapter: Stories of two men who pushed their luck.

Chapter 3: Never enough

When rich people do crazy things.

- The hardest financial skill is getting the goalpost to stop moving.

- Social comparison is the problem here. Ceiling of social comparision is so high that no one ever can hit it.

- It's a battle that can never be won.

- “Enough” is not too little. Idea of having "enough" might look like conservative, learving opportunity on the table, while it says that don't do a risky investment allocation you can't maintain.

- There are many things never worth risking, no matter the potential gain.

- Reputation is invaluable. Freedom and independence are invaluable.

- Family and friends are invaluable. Happiness is invaluable.

Next chapter: Building enough is remarkably simple.

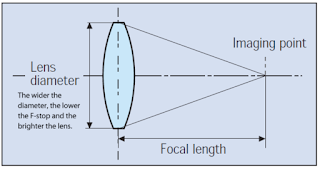

Chapter 4: Confounding Compounding

81.5 billion of Warren Buffett’s 84.5 billion net worth came after his 65th birthday. Our minds are not built to handle such absurdities

- Reason why Earth had iced ages, was there was a superpower?

- No, it starts when a summer never gets warm enough to melt the previous snow, leftover ice makes it easy for more snow to accumulate next winter.

- More snow reflecting more sun rays exacerbates cooling, bringing more snowfall and on and on.

- The big takeaway from ice ages is that you don't need tremendous force to

- create tremendous results.

- Good investing is earning pretty good returns that you can stick with and which can be

- repeated for the longest period of time.

- That's when compounding runs wild.

Next chapter: Earning good returns that can’t be held onto - leads to some tragic stories.

Chapter 5: Getting wealthy vs Staying wealthy

Good investing is not necessarily about making good decisions. It’s about consistently not screwing up.

- On 1929, made Jesse Livermore one of the richest men in the world. It ruined Abraham Gemansky.

- Four years down the line, stories cross paths again, Livermore overflowing with confidence, made larger and larger bets. Increasing amount of deb, and eventually lost everything in the stock market.

- They were both good at getting wealthy and equally bad at staying wealthy.

- Compounding only works if you can give an asset years and years to grow. But getting and keeping that extraordinary growth requires surviving all the unpredictable ups and downs that everyone inevitable experiences over time.

- He didn't get carried away with debt.

- He didn't panic and sell during the 14 recessions he's lived through.

- He didn't sully his business reputation.

- He didn't attach himself to one stretegy.

- He didn't rely on other's money

- He didn't burn himself out and quit or retire.

- He survived.

- More than I want big returns, I want to be financially unbreakable. And if I’m unbreakable I actually think I’ll get the biggest returns, because I’ll be able to stick around long enough for compounding to work wonders.

- Planning is important, but the most important part of every plan is to plan on the plan not going according to plan.

- - To predict returns for next 20 years, thing about all the big events that's happened in last 20 years.

- - A plan is only useful if it can survive reality. And a future filled with unknowns is everyone's reality.

- - A good plan doesn't pretend this weren't true, it embraces it and emphasis room for error.

- - The more you need specific elements of a plan to be true, the more fragile your financial life becomes.

- Eg: It'd be great if the market returns 8% a year for next 30 years, but if it does only 4% I'll still be OK

- A barbelled personality:

The idea that something can gain over the long run while being a basketcase in the short run is not intuitive, but it's how a lot of things work in life.

A mindset that can be paranoid and optimistic at the ame time is hard to maintain, because seeing things as black or white takes less effort than accepting nuance. But you need short term paranoid to keep you alive long enough to exploit long term optimism. Next, we’ll look at another way growth in the face of adversity can be so hard to wrap your head around.

Chapter 6: Tails, you win

You can be wrong half the time and still make a fortune.

- An investor can be wrong half the time and still make a fortune. It means we underestimate how normal it is for a lot of things to fail. Which causes us to overreact when they do.

- Anything that is huge, profitable, famous or influential is the result of a tail event - an outlying one-in-thousand event.

- Tails drives everything. Like out of 50 investments a VC make, 25 fails, 10 do well, 1-2 to be bonanzas that drive 100%of the fund returns.

- 40% of companies in index were effectively failures. but 7% of components that performed extremely well were more than enough to offset the duds.

- Not only few companies account for most of the market's return, but within those companies are even more tail events.

- When you realise tails drive everything in business, investing and finance, you realise that it's normal for lots of things to go wrong, break, fail and fall.

- Investors and entrepreneurs don't make good decisions all the time.

- Warren Buffett has owned 400-500 stocks and made most of his money on 10 of them.

- We pay special attention to a role model's successes we overlook that their gains came from a small percent of their actions. That make our own failure/losses feel like we're doing something wrong. Our masters may have been more right when they were right but they could have been wrong just as often as you.

Next chapter: How money can make you even happier.

Chapter 7: Freedom

Controlling your time is the highest dividend money pays.

- The ability to do what you want, when you want, with who you want, for as long as you want, is priceless.

- Happy people can't be grouped by income/geography/education.

- Six months of emergency fund means not being terrified of your boss, because you know you won't be ruined if you have to take some time off to find a new job.

- A reason of unhappiness if we've used our greater wealth to buy bigger and better stuff. But we've simultaneously given up more control over our time. At best those things cancel out each other.

- Most of us have jobs that rely on your thoughts as much on your actions, which means our days don't end when we clock out and leave the workspace. We're constantly working in our head, which means it feels like work never ends.

- In 30 Lessons for living, interviewed 1000 elderly Americans:

- No one, not a single person out of a thousand said that to be happy you should try to work as hard as you can to make money to buy the things you want.

- No one, not a single person, said it's important to be at least as wealthy as the people around you.

- No one, not a single one said you should choose your work based on your desired future earning power.

- What they did value were things like quality friendship, being part of something bigger than themselves and spending quality, unstructured time with their children.

- Controlling your time is the highest dividend money pays.

Next chapter: On one of the lowest dividends money pays.

Chapter 8: Man in the car Paradox

No one is impressed with your possessions as much as you are.

- When you see someone driving a nice car, you rarely think "Wow the guy driving that car is cool". Instead you think, "Wow, if I had the car people would think I'm cool".

- You might think you want an expensive car, a fancy watch, and a huge house. But I'm telling you, you don't.

What you want is respect and admiration from other people, and you think having expensive stuff will bring it. - And it applies to big house/ jewellery/ luxary items.

- The point here is not to abandon the persuit of wealth. If respect and admiration are you goal, be careful how you seek it. Humality, kindness and empathy will bring you more respect than horsepower ever will.

Next Chapter: Paradox about fast cars

Chapter 9: Wealth is what you don’t see.

Spending money to show people how much money you have is the fastest way to have less money.

- Someone driving a 100k car might be wealthy but the only data point you have about their wealth is that they have 100k less than they did before they bought the car (or in debt).

- Rich is current income.

- Wealth is hidden. Wealth is nice car not purchased. It’s income not spent. Its value lies in offering options, flexibility, and growth to one day purchase more stuff than you could right now.

- This is why it’s easy to find rich role model but hard to find wealthy ones because their success is more hidden. There are wealthy people who spent a lot but even in those cases what we see is their richness, not wealth.

Next Chapter: If wealth is what you don’t spend, what good is it? Well, let me convince you to save money.

Chapter 10: Save money

The only factor you can control generates one of the only things that matters. How wonderful.

- The biggest reason we overcame the oil crisis is because we started building card, factories that are more energy efficient than they used to be. The world grew it’s “energy wealth” not by increasing the energy (not in our control) it had but buy decreasing the energy it needed (largely in our control).

- Investment strategy will work/not is not in our control but personal savings are in our control.

- More importantly, the value of wealth is relative to what you need.

- Professional investor spend 80 hours a week to add 0.1% to returns while 2-3% of lifestyle bloat in thier finances that can be exploited with less effort.

- Past a certain level of income, what you need is just what sits below your ego.

- So people’s ability to save is more in their control than they might think.

- Savings -> spending less -> Desire less -> care less what others think of you

- And you don’t need a specific reason to save.

- Intangible benefits of money can be far more valuable and capable of increasing your happiness than tangible things

- That flexibility and control over your time is an unseen return on wealth.

Next chapter: Stop trying to be so rational.

Chapter 11: Reasonable > Rational

Aiming to be mostly reasonable works better than trying to be coldly rational.

- Reasonable is more realistic and you have a better chance of sticking with it for the long run, which is what matters most when managing money.

- We have evidence that fever turn on the body’s immune system, 100-104 degree are good for sick children. But fever is almost universally seen as a bad thing, they are treated with drugs to reduce it as quickly

- If fevers are beneficial, why do we fight them so universally? Fever hurd, and people don’t want to hurt. A doctor goal is not just to cure, it’s to cure within the confines of what’s reasonable and tolerable to the patient.

- For investment: People don’t want the math strategy, they want the strategy that maximises for how well they sleep at night.

Chapter 12: Surprise

History is the study of change, ironically used as a map of the future.

- Things that have never happened before happen all the time.

- History is mostly the study of surprising events. But is often used by investors and economists as an unassailable guide to the future.

- History helps us calibrate our expectations, study where people tend to go wrong, and offers a rough guide of what tends to work. But it is not, in any way, a map of the future.

- Imagine how much harder physics would be if electrons had feelings. Investors have feelings.

- Two most dangerous things happen when you rely too heavily on investment history as a guide to what's going to happen next.

- You’ll likely miss the outlier events that move the needle the most.

The correct lesson to learn from surprises is that the world is surprising. We should use past surprises as an admission that we have no idea what might happen next. - History can be a misleading guide to the future of the economy and stock market because it doesn’t account for structural changes that are relevant to today’s world.

- Many investors and economists take comfort in knowing their forecasts are backed up by decades of data. But since economies evolve, recent history is often the best guide to the future, because it's more like to include important conditions that are relevant to the future.

- Most common phrase used in investing, usually used mockingly, that "It's different this time."

Next chapter: How should we think about and plan for the future?

Chapter 13: Room for error

The most important part of every plan is planning on your plan not going according to plan.

- In Blackjack, by tracking what cards already been dealt, you can calculate what cards remain in the deck, and can tell the odds of a particular card being drawn by the dealer.

- By doing so, you bet when more odds are in your favor. But nothing is certain. There is always a chance, may be very small, it may not go in your favor.

- But bet too heavily when odds are in your favor and if they're wrong, you might lose so much that you don't have enough money to keep playing.

- There is never a moment when you're so right that you can bet every chip in front of you.

- The wisdom in having room for error is acknowledging that uncertainity, randomness, and chance, are an every present part of life. The only way to deal with them is by increasing the gap between what you think will happen and what can happen while still leaving you capable of fighting another day.

- Benjamain Graham's margin of safety concept: we don't need to view the world in front of us as black or white, predictable or a crapshoot. The grey area - pursuing things where a range of potential outcomes are acceptable - is the smart way to proceed.

- Two things cause us to avoid the room for error.

- Idea that somebody must know what the future holds, driven by the uncomfortable feeling that comes from admitting the opposite.

- You're doing harm to yourself by not taking actions that fully exploit an accurate view of that future coming true.

- Room for error is often seen as being conservative by those who don't want to take risks. But it's quite the opposite.

- Bill Gates: I wanted to have enough money in bank to pay a year's worth of payroll even if we didn't get any payments coming in.

- Some points for room for error:

- Valatility. Can you survive your assets declining by 30%? On a spreadsheet, maybe yes. But what about mentally? It is easy to underestimate what a 30% decline does to your pshyche. You may start looking for another career / new plan.

- Another reason is saving for retirement. US market have have 7.8% since 1870 inflation adjusted. But what if future returns are lower. What if your retirement ends up falling in the middle of a war?

- You may not be able to retire the way you planned it to go.

- Solution: Use room for error. Use 30% lower return as margin for error. It maygo even lower but no margin for error give 100% cover.

- I take barbell approach. I take risk with one part and I'm conservative with another. Just want to stand long term enough to pay for risks.

Next chapter: Planning on your plan not going according to plan. How this applies to you.

Chapter 14: You’ll change

Long-term planning is harder than it seems because people’s goals and desires change over time.

- Every five year old boy wants to drive a tractor when they grow up.

- Then the goals change from tractor to lawyer.

- After facing long working hours as lawyer, they take lower paying job with flexible hours.

- Then they realise childcare is expensive and it take all of their paychecks

- And at age 70, they realise they're unprepared for retirement.

- It's hard to make enduring long-term decisions when your view of what you'll want in the future is likely to shift.

- An illusion that history, our personal history, has just come to an end, that we have just recently become the people that we were always meant to be and will be for the rest of our lives.

- First rule of compounding says, don't interrupt it unnecessarily. Many of us evolve so much over a lifetime that we don't want to keep doing the same thing for decades on end.

- Two things to keep in mind for making what you think is long term decisions:

- We should avoid the extreme ends of financial planning. We should avoid the extreme ends of financial planning.

One end: The simplicity of having hardly anything.

Other end: The thrill of having almost everything. - Compounding applies not only for saving but careers and relationships.

- We should also come to accept the reality of changing our minds.

Odds of picking a job when you're not old enough to when you get old, is low. - Sunk cost: Anchoring decisions to past efforts that can't be refunded, are a decil in a world where people change over time.

Next chapter: Compounding’s price of admission.

Chapter 15: Nothing’s Free

Everything has a price, but not all prices appear on labels.

- If you want to buy car, you have three options:

- Pay $30, 000, cost of car

- Find a cheaper used one

- Steal it.

- 99% will avoid the third option, but while plan to 11% of return, does this reward come free? It's NOT.

- The price is

- Volatility

- Fear

- Doubt

- Uncertainity

- Regret

- Like the car, you have 3 options:

- Pay the price, accept volatility and upheaval

- Find a less uncertain asset

- Try to get the return while avoiding the volatility that comes along

- Many people choose the third option. They form tricks and strategies to get the return without paying theprice. They attempt to sell before next recession and buy before next boom. Some car thieves will get away while others will be caught and punished.

- Example: Techtical mutual funds, they switch b/w stocks and bonds at opportunate times. They want returns without paying the price. One study revealed 9 out of 112 didn't perform better than just 60/40 simple stock bond fund.

- Why do so many people ready to pay the price of cars, houses, food and vacations but try to avoid paying the prices of good investment returns?

- Answer is simple, price of investment is not immediately obvious. It doesn't look a fee, it feels like a fine for doing something wrong.

Chapter 16: You & me

Beware taking financial cues from people playing a different game than you are.

- People make financial decision they regrest and they often do so with scarce information and without logic. But the decisions made sense to them when there were made.

- No one wants to think they own an overvalued asset.

- Investors often innocently take cues from other investors who are playing a different game than they are.

- How much you should pay for Google stock today? The answer depend on who "you" are?

- Do you have a 30 years time horizon? Smart price involves analysis of Googles's discounted cash flows over the next 30 years.

- 10 years? Analysis of tech industry over the next decade? Weather Google management can execute on its vision?

- Within a year? See Google current product sales cycles and weather we'll have a bear market?

- Day trader? "Who cares".

- Yahoo stock in 1999, people say it's a zillion times revenue, valuation made no sense. But many investors had time horizon so small, it made sense to them.

- If an asset has momentum, it's been moving consistently up for a period of time, it's not crazy for short term trader.

- Bubbles form when the momentum of short-term returns attracts enough money that the makeup of investors shifts from mostly long term to mostly short term.

- Bubbles do their damage when long-term investors playing one game start taking their cues from those short-term traders playing another.

- Maybe these other investors know something I don't. Maybe you were along with it. You even felt smart about it. But you planned on holding shares for the long run.

- When a commentator on CNBR says" You should buy this stock," keep in mind that they do not know who you are.

Chapter 17: The Seduction of Pessimism

Optimism sounds like a sales pitch. Pessimism sounds like someone trying to help you.

Optimism is the best bet for most people because the world tends to get better for most people most of the time. Pessimism isn't just more common but paid more attention than Optimism.

- An article on Dec 29, 2008:

- Around the end of June 2010, US will break into six pieces. Alaska reverting to Russia control, California will be a part of China, Texas will go to Mexico.

- This was on the front page of the most prestigious financial newspaper in the world.

- It's fine to be pessimistic about the economy.

- Interesting thing is, their polar opposite - forecasts of outrageous optimism - are rarely take as seriously as prophets of doom.

- Take Japan in the late 1940, defeated in WWII. Imagine a newspaper article during that time:

- Within our lifetime, our economy will grow 15 times to pre-war times.

- Life expantancy will double.

- Stock will product more than any other country in the world.

- 40 year, unemployment less than 6%.

- And so on...

- They would have been summarily laughed out of the room and asked to seek a medical evalution.

- Keep in mind this is what actually happened in Japan after the war.

- If a smart person tells me they a stock pick that's going to rise 10 times, I will write them off as full of nonsense.

- If someone who's full of nonsense tells me that a stock I own is about to collapse because it's an accounting fraud, i will clear my calender and listen their every world.

- When directly compared against each other, losses loom larger than gains.

- Organisns that treat threats as more urgent than opportunities have a better chance to survive and reproduce.

Few things make financial pessimism easy, common, and more persuasive than optimism.

- One is that money is ubiquitous, so something bad happening tends to affect everyone and captures everyone’s attention.

- A recession barreling down on the economy coould impact every single person. Even if you hold stocks or not.

- Two topics will always effect your life, whether you are interested in them or not:

- Money and Health.

- Another is that pessimists often extrapolate present trends without accounting for how markets adapt.

- "By 2030, China would need 98M battels oil a day, world is producing 85M. We may never produce much more than that". This was an extreme end, that' now how markets work.

- Extreme googd/bad circumstances rarely stay that way for long because supply/demand adapt in hard to predict way.

- Oild price surged, makes drilling like pulling gold out of ground and also more oil efficient machines.

- A third is that progress happens too slowly to notice, but setbacks happen too quickly to ignore.

- Growth is driven by compounding, which takes time.

- Destruction is driven by single points of failure, which can happen in seconds.

- It's easier to make a narrative around pessimism because the story pieces tend to be fresher.

- Optimistic developments which people tend to forget, and take more effort to piece together.

- Eg. Wright brother made their first flight successfull.

- Eg. A 40% dip in 6 months takes more attention than 140% rise in 6 years.

Chapter 18: When you’ll believe anything

Appealing fictions, and why stories are more powerful than statistics.

- An alien visiting earth on 2007 and 2009 found no difference.

- But when he looked at the numders

- Households are $16 trillion poorer in 2009 than there were in 2007.

- 10 million more Americans are unemployed.

- The stock market worth is half.

- There was one change the Alien couldn't see b/w 2007 and 2009.

- The stories we told ourselves about the economy.

- In 2007 we told a story about the stability of housing prices, the stability of financial markets to accurately price risk.

- In 2009, we stopped believing that story.

- Once the narrative that home prices will keep rising broke, mortgage defaults rose, then banks lost money, they reduced lending to other businesses, which led to layoffs, which led to less spending, which led to more layoffs, and on and on.

- When we think about the growth of economics, businesses, investments and careers, we tend to think about tangible things - how much stuff do we have, what we are capable of?

- But stories, by far, the most powerful force in the economy.

- The more you want something to be true, the more likely you are to believe a story that overestimates the odds of it being true.

- This may sound crazy but if you desperately need a solution and a good one isn't known or readily available to you, the path of least resistance is "you'll believe anything".

- Like:

- When you have no money, and your son is sick, you'll believe anything.

- Investing, since stakes are so high.

- Since stakes are so high, get a few stock picks right and you can become rich without much effort. If there's 1% chance that some tip/stock pick will change your life, it's not craze to pay attention to it.

- In 2007, Federal Reserve growth prediction was 1.6%-2.8%. That was it's margin of safety, it's room for error. In reality it was -2%, lower than 3x.

- It's hard for policymakers to predict an outright recession, because a recession will make their careers complicated. So worse case projections rarely expect anything worst than just slow-ish.

- If you think a recession is coming and you cash out your stocks in anticipations, your view of economy is suddenly warped by what you want to happen. Every dip/ancedote, will look like a sign that doom has arrived - maybe not because it has, but you want it to.

- Everyone has an incomplete view of the world. But we form a complete narrative to fill in the gaps.

- Like the daughter of the author, fits everything into her already-known models.

- Even though she knows a little, shes doesn't realise, because she tells herself a coherant story about what's going on based on little she does know.

- Forecasting the stock marking and the economy is so hard because you are the only person in the world who thinks the world operates the way you do.

- If you assume that the market goes up every year by it's historic average, your accuracy is better than average annual forecasts of top 20 market strategies from large wall street banks.

- Since big events come out of nowhere, forcasters do more harm than good by providing the illusion of predictability.

- When planning, we focus on what we want to do and can do, neglecting the plans and skills of others whose decisions might affect our outcomes.

- In explaining the past and also in predicting the future, we focus on casual role of skills and neglect the role of luck.

- We focus on what we know and neglect what we do not know, which makes us overly confident in our beliefs.

Chapter 19: All Together Now

What we’ve learned about the psychology of your own money.

- Go out of your way to find humility when things are going right and forgiveness/compassion when they go wrong.

=> Respect the power of luck and risk and you'll have a better chance of focusing on things you can actually control. - Less ego more wealth.

=> You'll never build wealth unless you can put a lid on how much fun you can have with your money right now, today. - Manage your money in a way that helps you sleep at night.

=> Some people won't sleep well unless they're earning the highest returns, other will only get a good sleep if they're conservatively invested. - If you want to do better as an investor, the single most powerful thing you can do is increase your time horizon.

- Become OK with a lot of things going wrong. You can be wrong half the time and still make a fortune.

=> You should always measure how you've done by looking at your full portfolio rather than individual investments. - Use money to gain control over your time.

=> Ability to do what you want, when you want, with whom you want, for as long as you want to, pays the highest divident - Be nicer and less flashy.

=> No one is impressed with your luxary car as much you are. You probably want respect, kindness is a better way to get it. - Save. Just save. You don’t need a specific reason to save.

- Define the cost of success and be ready to pay it

=> Uncertainity, doubt and regret are common costs in the finance world, see them as fee not fine. - Worship room for error.

=> Keeps you in game for longer. - Avoid the extreme ends of financial decisions.

=> We will change over time, more extreme our past decisions are, more we regret as we evolve. - You should like risk because it pays off over time.

- Define the game you’re playing.

=> Make sure your actions are not being influenced by people playing a different game. - Respect the mess.

=> Smart, informed and reasonable people can disagree in finance, because people have vastly different goals and desire. There is no right answer, just the answer that works for you.

Chapter 20: Confessions

The psychology of my (author) money.

- How my family thinks about savings

- I mostly just want to wake up every day knowing my family and I can do whatever we want to do on our own terms.Every financial decision we make revolves around that goal.

- Independence at any level, is driven by your savings rate. Past a certain level of income your savings rate is driven your ability to keep your lifestyle expectations from running away.

- We like nice stuff and live comfortable. We just got the goalpost to stop moving.

- True success is exiting some rat race to modulate one’s activities for peace of mind.

- Good decisions aren’t always rational. At some point you have to choose between being happy or being “right”.

- How my family thinks about investing

- Beating the market should be hard, the odds of success should be low. If they weren’t, everyone would do it, and if everyone did it there would be no opportunity.

- We will have a high chance of meeting all of our family’s financial goals if we consistently invest money into a low cost index fund for decades.

- If you can meet all your goals without having to take the added risk that comes from trying to outperform the market, then what’s the point of even trying?

- Simple investment strategies can work great as long as they capture the tail events.

- My investment strategy doesn’t rely on picking the right sector, or timing the next recession. It relies on a high savings rate, patience, and optimism that the global economy will create value over the next several decades.

- I’ve changed my investment strategy in the past. So of course there’s a chance I’ll change it in the future.

- No matter how we save or invest. I’m sure we’ll always have the goal of independence, and we’ll always do whatever maximizes for sleeping well at night.

Postscript: A Brief History of Why the U.S. Consumer Thinks the Way They Do.

- Inside bill's brain (Netflix documentory)

- 30 Lessons of living by Karl Pillermer (Chapter 7, #89)

- The intelligent investor by benjamin graham (Chapter 12, #130)

- Is this still related?

- It has old concepts which may be not relevant now? As auther says

- Thinking fast and slow by Danial Kahneman (Chapter 14, #153)

- The Rational Optimist by Matt Ridley (Chapter 17, #180)

- Documentary: How to live forever (Chapter 18, #193)

Comments

Post a Comment